9 Personal access token for HTTPS

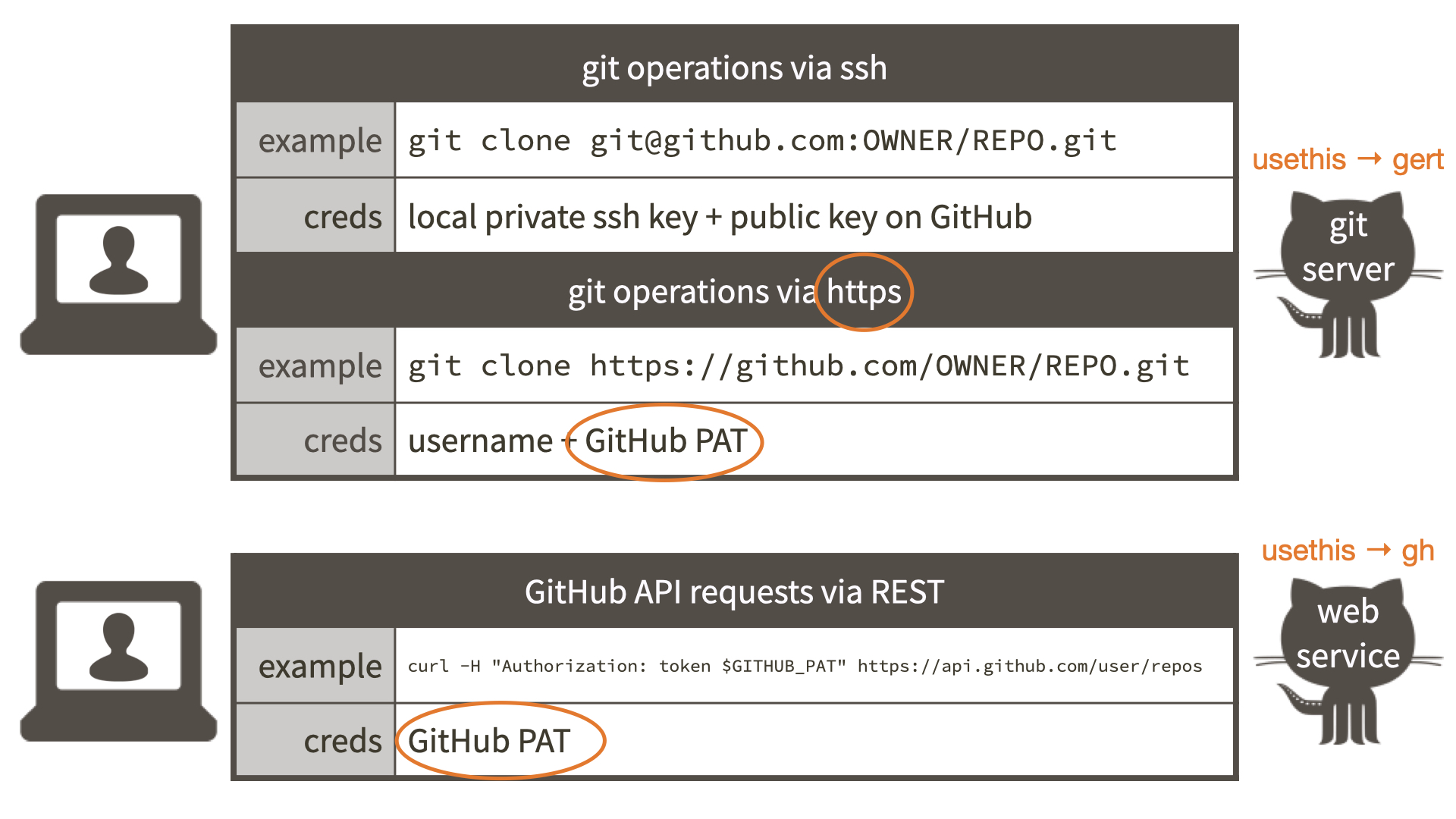

When we interact with a remote Git server, such as GitHub, we have to include credentials in the request. This proves we are a specific GitHub user, who’s allowed to do whatever we’re asking to do.

Git can communicate with a remote server using one of two protocols, HTTPS or SSH, and the different protocols use different credentials.

Here we describe the credential setup for the HTTPS protocol, which is what we recommend if you have no burning reason to pick SSH. With HTTPS, we will use a personal access token (PAT). Head over to chapter 10 if you really want to set up SSH keys.

Let it be known that the password that you use to login to GitHub’s website is NOT an acceptable credential when talking to GitHub as a Git server. This was possible in the past (and may yet be true for other Git servers), but those days are over at GitHub. You can learn more in their blog post Token authentication requirements for Git operations.

Here’s the error you’ll see if you try to do that now:

remote: Support for password authentication was removed on August 13, 2021. Please use a personal access token instead.

remote: Please see https://github.blog/2020-12-15-token-authentication-requirements-for-git-operations/ for more information.

fatal: Authentication failed for 'https://github.com/OWNER/REPO.git/'The recommendation to use a personal access token (PAT) is exactly what we cover in this chapter.

9.1 TL;DR

This is a very minimal account of getting and storing a PAT. This might be all you need when you’re first getting yourself set up. You can always come back later and read other parts of this chapter.

Go to https://github.com/settings/tokens and click “Generate token”.

Or, from R, do:

usethis::create_github_token()Look over the scopes; I highly recommend selecting “repo”, “user”, and “workflow”.

Recommended scopes will be pre-selected if you used create_github_token().

Click “Generate token”.

Copy the generated PAT to your clipboard. Or leave that browser window open and available for a little while, so you can come back to copy the PAT.

Provide this PAT next time a Git operation asks for your password2.

You could even get out ahead of this and store the PAT explicitly right now.

In R, call gitcreds::gitcreds_set() to get a prompt where you can paste your PAT:

gitcreds::gitcreds_set()Paste the PAT in response to the dialogue in the console:

? Enter password or token: ghp_xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

-> Adding new credentials...

-> Removing credentials from cache...

-> Done.You should be able to work with GitHub now, i.e. push and pull. If you’re still doing your initial setup, now is a great time to move on to Connect to GitHub.

Read on to learn more about:

9.2 HTTPS versus SSH

I find HTTPS easier to get working quickly and strongly recommend it when you first start working with Git/GitHub. HTTPS is what GitHub recommends, presumably for exactly the same reasons. The “ease of use” argument in favor of HTTPS is especially true for Windows users. I started with HTTPS, preferred SSH for a while, and have returned to HTTPS. The main thing to know is that this is not an all-or-nothing decision and it’s a relatively easy decision to revisit later.

Another advantage of HTTPS is that the PAT we’ll set up for that can also be used with GitHub’s REST API. That might not mean anything to you (yet), but there are many R packages that call GitHub’s API on your behalf (devtools+usethis, remotes, pak, gh, etc.). Configuring your PAT kills two birds with one stone: this single credential can be used to authenticate to GitHub as a regular Git server and for its REST API. If you authenticate via SSH for “regular” Git work, you will still have to set up a PAT for work that uses the REST API.

A properly configured PAT means all of this will “just work”:

- Remote HTTPS operations via command line Git and, therefore, via RStudio

- Remote HTTPS operations via the gert R package and, therefore, usethis

- GitHub API operations via the gh R package and, therefore, usethis

9.2.1 URL determines the protocol

Even though I’m suggesting that you adopt HTTPS as a lifestyle, it’s good to know that you actually have very granular control over the protocol. It is determined by the URL used to access a remote repo. Feel free to skip this section if you are new to Git (we mention some concepts and commands that won’t make much sense ’til you’ve used Git a little).

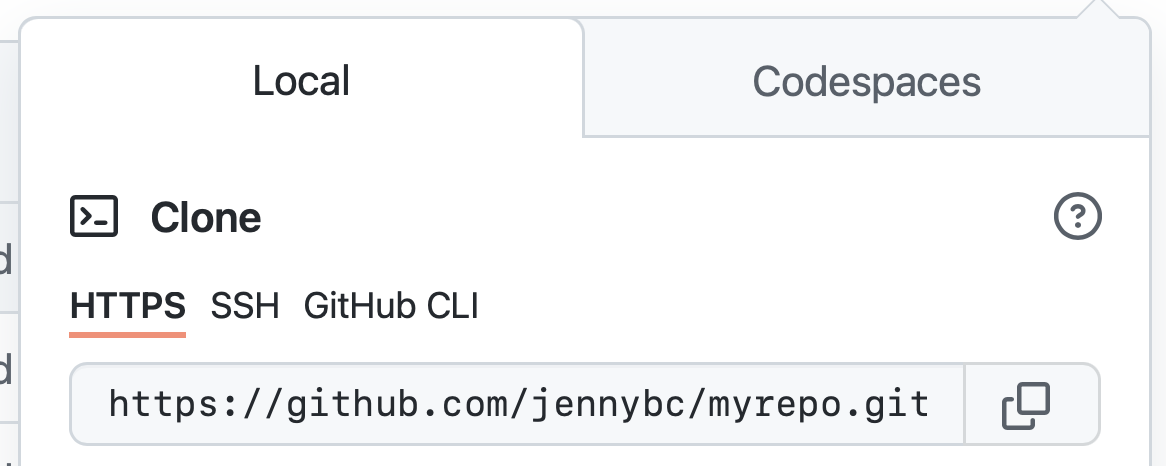

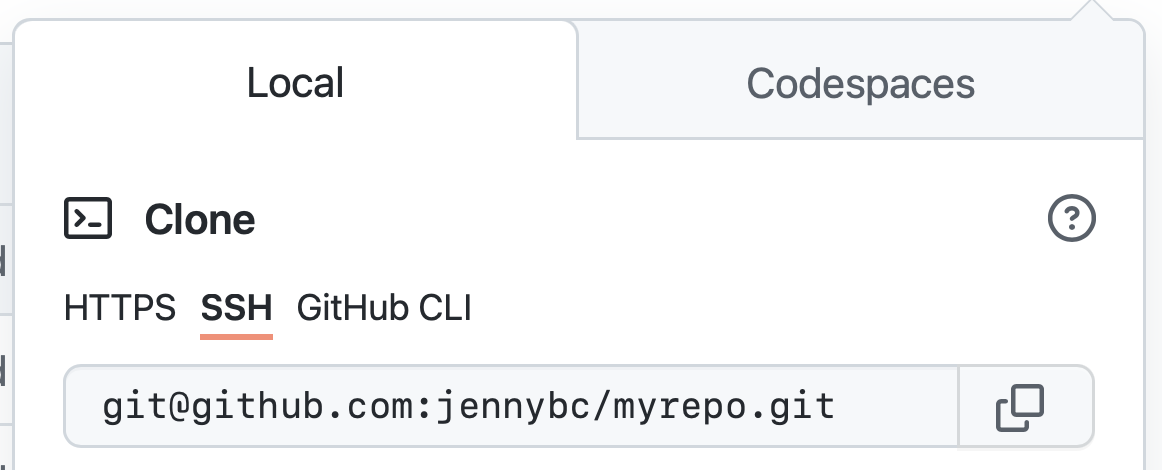

HTTPS remote URLs look like https://github.com/<OWNER>/<REPO>.git.

SSH remote URLs look like git@github.com:<OWNER>/<REPO>.git.

When you execute a command such as git push origin my-cool-feature-branch, Git looks up the URL you’ve stored for the origin remote and uses the protocol implicit in the URL’s format.

The protocol is a game time decision.

This implies that:

- It’s fine to use HTTPS for one remote in a repo and SSH for another.

- It’s fine to use HTTPS in one repo and SSH in another.

- It’s fine to interact with a GitHub repo via HTTPS from one computer and via SSH from another.

- It’s fine to adopt HTTPS for new work, even if some of your pre-existing repos use SSH.

You just have to be aware that mixed use of HTTPS and SSH means you’ll have to configure both sorts of credentials.

Changing a specific remote from HTTPS to SSH (and back again) is a straightforward operation with git remote set-url REMOTE_NAME DESIRED_URL:

~/rrr/happy-git-with-r % git remote -v

origin https://github.com/jennybc/happy-git-with-r.git (fetch)

origin https://github.com/jennybc/happy-git-with-r.git (push)

~/rrr/happy-git-with-r % git remote set-url origin git@github.com:jennybc/happy-git-with-r.git

~/rrr/happy-git-with-r % git remote -v

origin git@github.com:jennybc/happy-git-with-r.git (fetch)

origin git@github.com:jennybc/happy-git-with-r.git (push)

~/rrr/happy-git-with-r % git remote set-url origin https://github.com/jennybc/happy-git-with-r.gitWe can do the same from R using functions in usethis:

usethis::git_remotes()

#> $origin

#> [1] "https://github.com/jennybc/happy-git-with-r.git"

usethis::use_git_remote(

"origin",

"git@github.com:jennybc/happy-git-with-r.git",

overwrite = TRUE

)

usethis::git_remotes()

#> $origin

#> [1] "git@github.com:jennybc/happy-git-with-r.git"

usethis::use_git_remote(

"origin",

"https://github.com/jennybc/happy-git-with-r.git",

overwrite = TRUE

)9.3 Generate a personal access token (PAT)

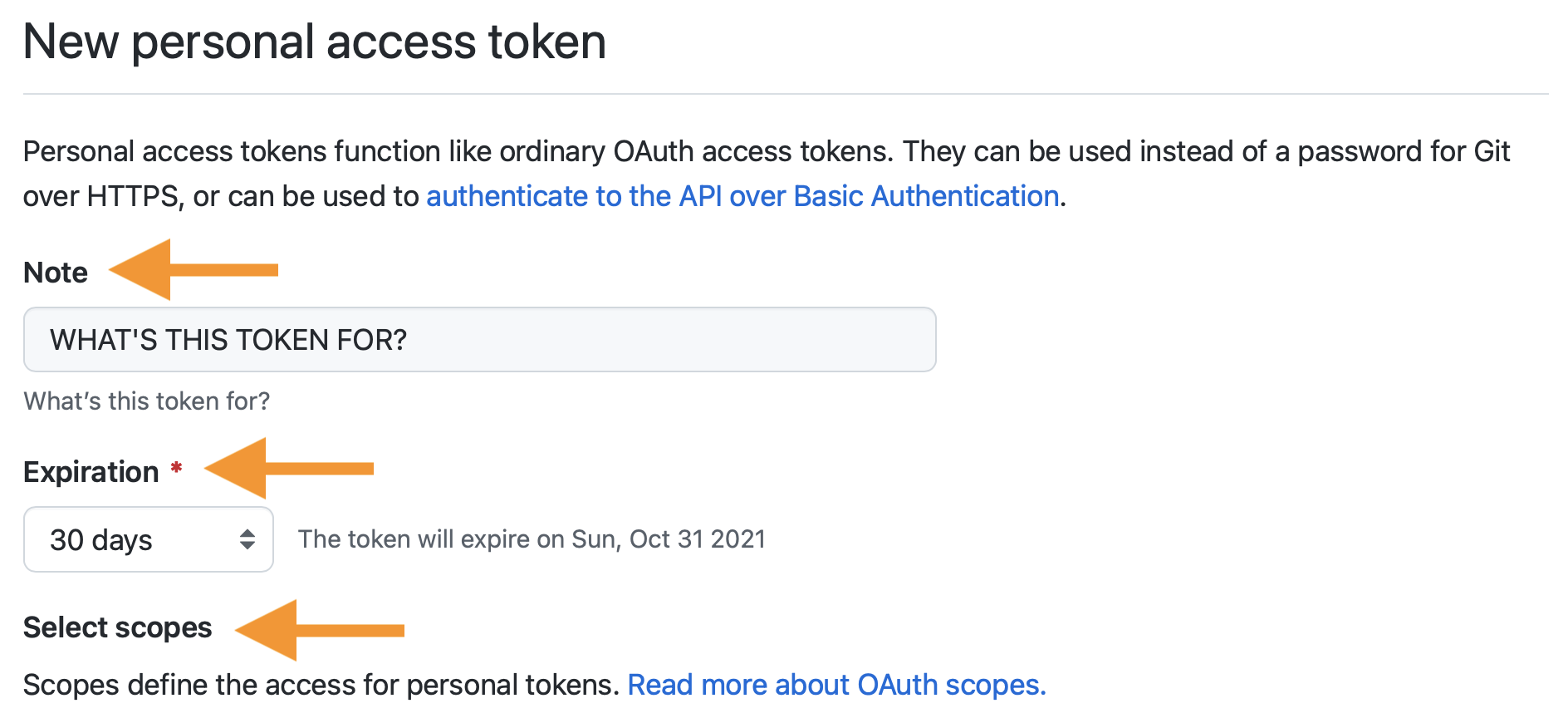

On github.com, assuming you’re signed in, you can manage your personal access tokens from https://github.com/settings/tokens, also reachable via Settings > Developer settings > Personal access tokens.

You could click on “Generate new token” here or, perhaps even better, you could call usethis::create_github_token() from R:

usethis::create_github_token()The usethis approach takes you to a pre-filled form where we have pre-selected some recommended scopes, which you can look over and adjust before clicking “Generate token”. At the time of writing, the usethis-recommended scopes are “repo”, “user”, “gist”, and “workflow”.

It is a very good idea to describe the token’s purpose in the Note field, because one day you might have multiple PATs. We recommend naming each token after its use case, such as the computer or project you are using it for, e.g. “personal-macbook-air” or “vm-for-project-xyz”. In the future, you will find yourself staring at this list of tokens, because inevitably you’ll need to re-generate or delete one of them. Make it easy to figure out which token you’ve come here to fiddle with.

GitHub encourages the use of perishable tokens, with a default Expiration period of 30 days. Unless you have a specific reason to fight this, I recommend accepting this default. I assume that GitHub’s security folks have good reasons for their recommendation. But, of course, you can adjust the Expiration behaviour as you see fit, including “No expiration”.

Once you’re happy with the token’s Note, Expiration, and Scopes, click “Generate token”.

You won’t be able to see this token again, so don’t close or navigate away from this browser window until you store the PAT locally. Copy the PAT to the clipboard, anticipating what we’ll do next: trigger a prompt that lets us store the PAT in the Git credential store.

Treat this PAT like a password! Do not ever hard-wire your PAT into your code! A PAT should always be retrieved implicitly, for example, from the Git credential store. We’re about to help you store the PAT in a safe place, where command line Git, RStudio, and R packages can discover it.

If you use a password management app, such as 1Password (highly recommended!), you might want to also add this PAT (and its Note) to the entry for GitHub, where you’re already storing your username and password. Storing your PAT in the Git credential store is a semi-persistent convenience, sort of like a browser cache or “remember me” on a website3 and it’s conceivable you will need to re-enter your PAT in the future. You could decide to embrace the impermanence of your PAT and, if it somehow goes missing, you’ll just re-generate the PAT and re-store it. If you accept the default 30-day expiration period, this is a workflow you’ll be using often anyway. But if you create long-lasting tokens or want to feel free to play around with the functions for setting or clearing your Git credentials, it can be handy to have your own record of your PAT in a secure place, like 1Password.

9.4 Store your PAT

At this point, I assume you’ve generated a PAT and have it available, in one or both of these ways:

- In a secure, long-term system for storing secrets, like 1Password

- For the next few minutes, in a browser window or on the clipboard

There are a couple ways to get your PAT into the Git credential store:

- Call an R function to explicitly store (or update) your credentials.

- Do something in command line Git or RStudio that triggers a credential challenge.

9.4.1 Call an R function to store your credentials

There are two R packages for accessing the Git credential store:

It is likely that these packages will eventually combine into one and, even now, they are largely interoperable. You don’t need to follow the instructions for both packages – pick one!

9.4.1.1 gitcreds package

If you don’t have gitcreds installed, install via install.packages("gitcreds").

If you’ve installed usethis, you will already have gitcreds, because usethis uses gh and gh uses gitcreds.

Call gitcreds::gitcreds_set().

If you don’t have a PAT stored already, it will prompt you to enter your PAT. Paste!

> gitcreds::gitcreds_set()

? Enter password or token: ghp_xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

-> Adding new credentials...

-> Removing credentials from cache...

-> Done.If you already have a stored credential, gitcreds::gitcreds_set() reveals this and will even let you inspect it.

This helps you decide whether to keep the existing credential or replace it.

When in doubt, embrace a new, known-to-be-good credential over an old one, of dubious origins.

> gitcreds::gitcreds_set()

-> Your current credentials for 'https://github.com':

protocol: https

host : github.com

username: PersonalAccessToken

password: <-- hidden -->

-> What would you like to do?

1: Keep these credentials

2: Replace these credentials

3: See the password / token

Selection: 2

-> Removing current credentials...

? Enter new password or token: ghp_xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

-> Adding new credentials...

-> Removing credentials from cache...

-> Done.You can check that you’ve stored a credential with gitcreds_get():

gitcreds_get()

#> <gitcreds>

#> protocol: https

#> host : github.com

#> username: PersonalAccessToken

#> password: <-- hidden -->Other functions that can help you feel confident about your PAT setup include:

usethis::gh_token_help()

usethis::git_sitrep()

gh::gh_whoami()9.4.1.2 credentials package

If you don’t have credentials installed, install via install.packages("credentials").

If you’ve installed usethis, you will already have credentials, because usethis uses gert and gert uses credentials.

Call set_github_pat().

If you don’t have a PAT stored already, it will prompt you to enter your PAT. Paste!

credentials::set_github_pat()If successful, your initial (and subsequent) calls will look like this:

credentials::set_github_pat()

#> If prompted for GitHub credentials, enter your PAT in the password field

#> Using GITHUB_PAT from Jennifer (Jenny) Bryan (credential helper: osxkeychain)Other functions that can help you feel confident about your PAT setup include:

usethis::gh_token_help()

usethis::git_sitrep()

gh::gh_whoami()9.4.2 Store credentials through organic Git use

Before gitcreds and credentials existed (see above), we had to orchestrate a credential challenge by setting up (and then tearing down) a toy repo.

That still occurs naturally in the guided exercise in Connect to GitHub.

But I strongly recommend managing your PAT more directly and explicitly with

gitcreds::gitcreds_set() and related functions in gitcreds.

9.5 HTTPS PAT problems and solutions

This section is for people who need to know even more about PAT management, because they’re in a nonstandard situation or troubleshooting.

9.5.1 Valid PAT gets stored, but later told the PAT is invalid

Let’s say you generate a fresh PAT and successfully store it as described above. Maybe you even use it successfully. But later, you’re told your PAT is invalid! How can this be?

Here are some likely explanations:

- Your PAT truly is invalid. By default, PATs have an expiration date now. One day you really will wake up and find the PAT has gone bad overnight and you need to re-generate and re-store it.

- You have an invalid PAT stored somewhere else, that you’ve forgotten about,

probably in

.Renviron. This old, invalid PAT is preventing R packages from even discovering your new, valid PAT.

9.5.1.1 PAT has expired

You are going to be re-generating and re-storing your PAT on a schedule dictated by its expiration period. By default, once per month.

When the PAT expires, return to https://github.com/settings/tokens and click on its Note.

(You do label your tokens nicely by use case, right? Right?)

At this point, you can optionally adjust scopes and then click “Regenerate token”.

You can optionally modify its Expiration and then click “Regenerate token” (again).

As before, copy the PAT to the clipboard, call gitcreds::gitcreds_set(), and paste!

Hopefully it’s becoming clear why each token’s Note is so important. The actual token may be changing, e.g., once a month, but its use case (and scopes) are much more persistent and stable.

9.5.1.2 Old GITHUB_PAT in .Renviron

These usethis functions will diagnose this problem:

usethis::gh_token_help()

usethis::git_sitrep()In the past, it was common to store a PAT as the GITHUB_PAT environment variable in .Renviron.

But now, thanks to gitcreds and credentials, we can store and retrieve a PAT, from R, the same way as command line Git does.

If you have any doubt about your previous practices, open .Renviron, look for a line setting the GITHUB_PAT environment variable, and delete it. usethis::edit_r_environ() can be helpful for getting .Renviron open for editing.

Don’t forget to restart R for this change to take effect.

9.5.2 PAT doesn’t persist on macOS or Windows

The credential helpers used by Git take advantage of official OS-provided credential stores, where possible, such as macOS Keychain and Windows Credential Manager.

If you’re trying to follow the advice here and your PAT never persists, consider that you may need to update Git to get its more modern credential helpers. This is absolutely an area of Git that has improved rapidly in recent years and the gitcreds and credentials package work best with recent versions of Git. I have not needed to explicitly activate a credential helper on macOS or Windows with any recent version of Git.

Here’s a command to reveal the current credential helper and what I see these days.

macOS

$ git config --show-origin --get credential.helper

file:/Users/jenny/.gitconfig osxkeychainWindows

$ git config --show-origin --get credential.helper

file:C:/Program Files/Git/mingw64/etc/gitconfig managerIf you want to know how gitcreds and credentials are managing your PAT, learn about git credential <fill|approve|reject>.

For keeners, that documentation gives you the gory details on how credentials are stored and retrieved:

Git has an internal interface for storing and retrieving credentials from system-specific helpers, as well as prompting the user for usernames and passwords. The

git-credentialcommand exposes this interface to scripts which may want to retrieve, store, or prompt for credentials in the same manner as Git.

On Windows, your Git credentials are probably being stored via Credential Manager.

On macOS, your Git credentials are probably being stored in the Keychain.

If you really want to poke around directly to explore or clean out your GitHub credentials, launch Credential Manager (Windows) or Keychain Access (macOS) and search for “github.com”.

9.5.3 PAT doesn’t persist on Linux

The credential helpers used by Git take advantage of official OS-provided credential stores on macOS and Windows, but sadly there is no exact equivalent on Linux.

The easiest thing to do is to configure Git to “cache” your credentials (vs “store”), which is more time-limited. Then set the cache timeout to some suitably long period of time. Here, we set the timeout to ten million seconds or around 16 weeks, enough for a semester.

git config --global credential.helper 'cache --timeout=10000000'This still may not make your PAT available to R packages.

In this case, you may need to use the older, less secure approach of storing your PAT in .Renviron.

usethis::edit_r_environ() opens that file for editing.

usethis::edit_r_environ()Add a line like this, but substitute your PAT:

Make sure this file ends in a newline! Lack of a newline can lead to silent failure to load startup files, which can be tricky to debug. Take care that this file is not accidentally pushed to the cloud, e.g. Google Drive or GitHub.

Restart R for changes in .Renviron to take effect.