24 Refs

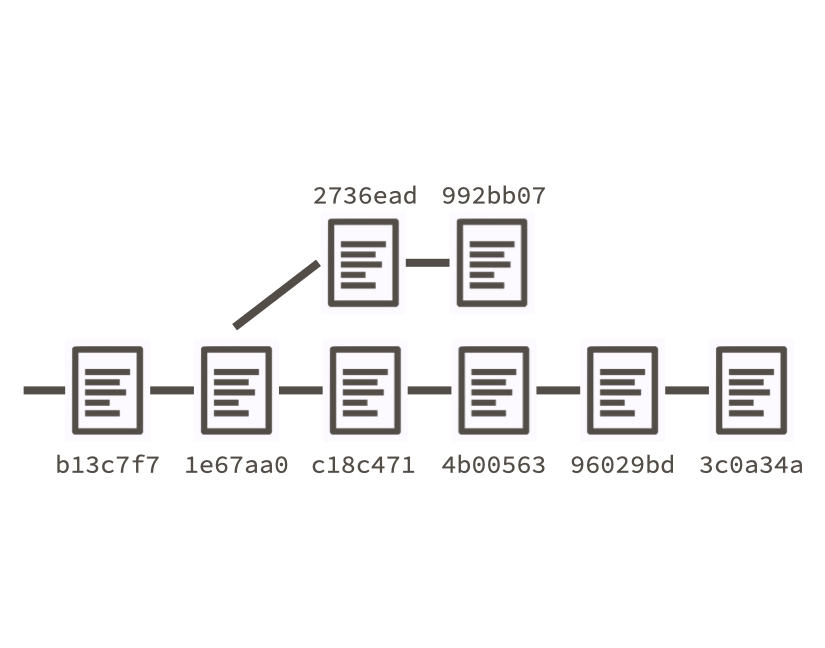

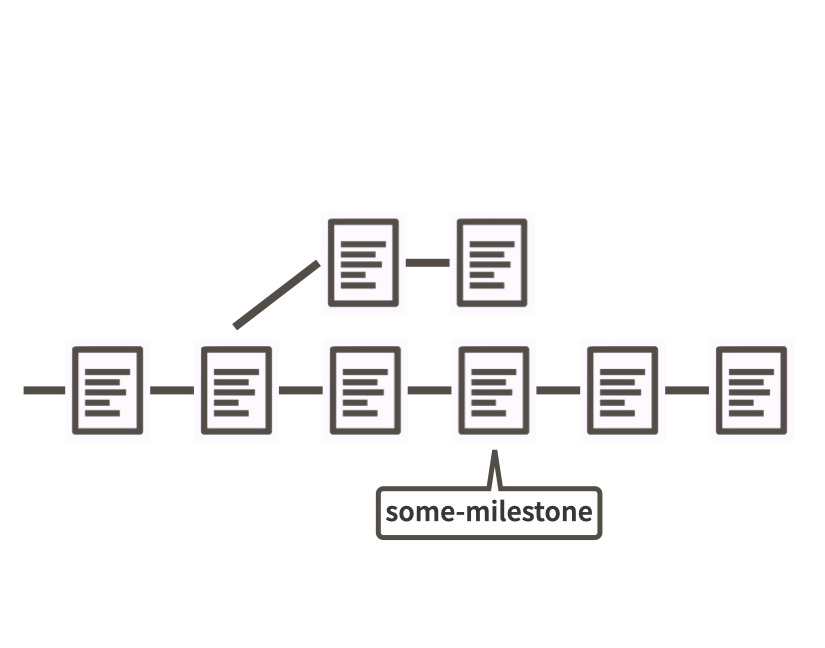

Many extremely useful Git workflows require you to identify a specific point in your repo’s history, i.e. a specific commit.

We’ve explained elsewhere that every commit is associated with a so-called SHA, i.e. a SHA-1 checksum of the commit itself. These opaque strings of 40 letters and numbers are not particularly pleasant for humans to work with. The entry-level coping strategy is to work with an abbreviated form of the SHA. It’s typical to only use the first 7 characters, as this almost always uniquely identifies a commit.

Luckily, there are even more ways to talk about a specific commit, that are much easier for humans to wrap their head around. These are called Git “refs”, short for references and, if you’re familiar with the programming concept of a pointer, that’s exactly the right mental model.

24.1 Useful refs

Here are some of the most useful refs:

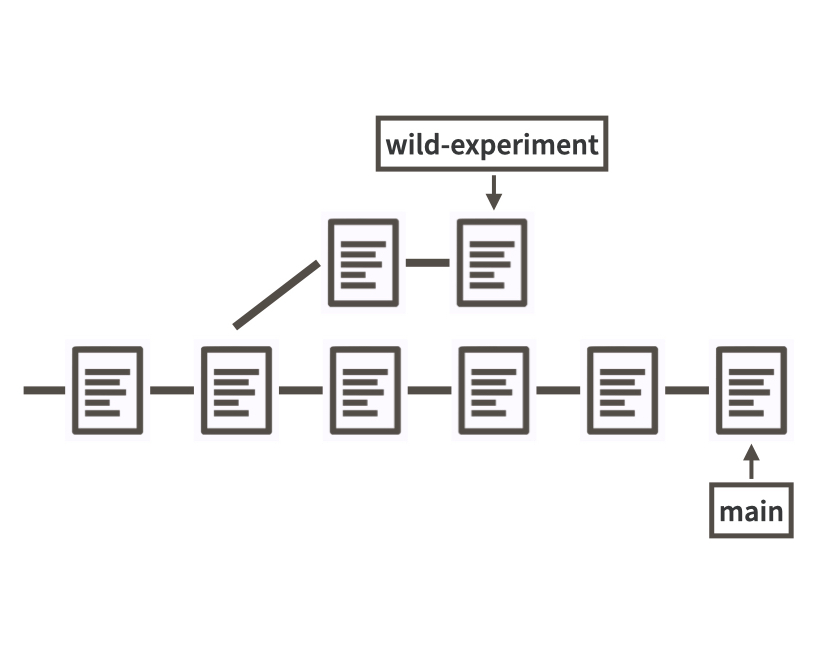

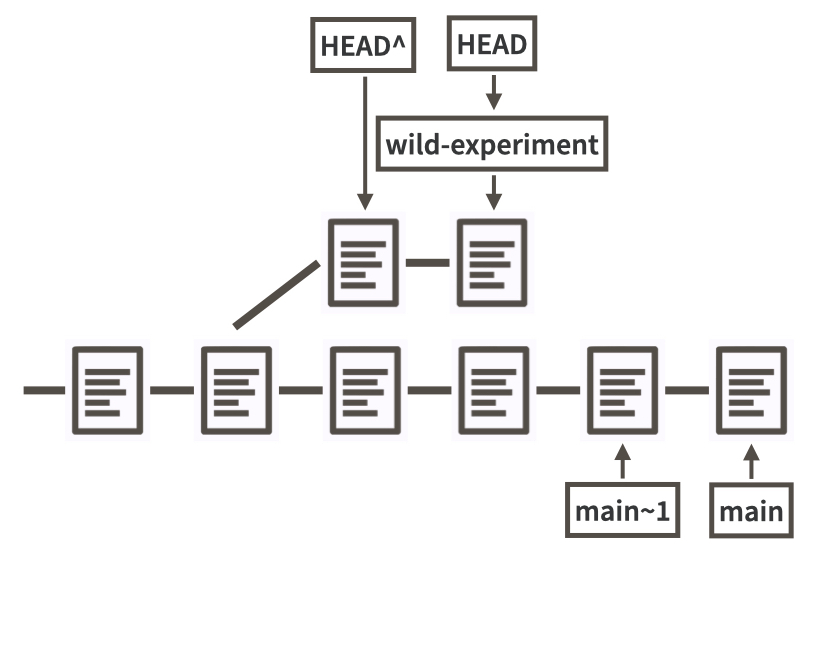

- A branch name.

Example:

main,wild-experiment. When you refer to themainbranch, that resolves to the SHA of the tip of themainbranch. Think of a branch ref as a sliding ref that evolves as the branch does.

-

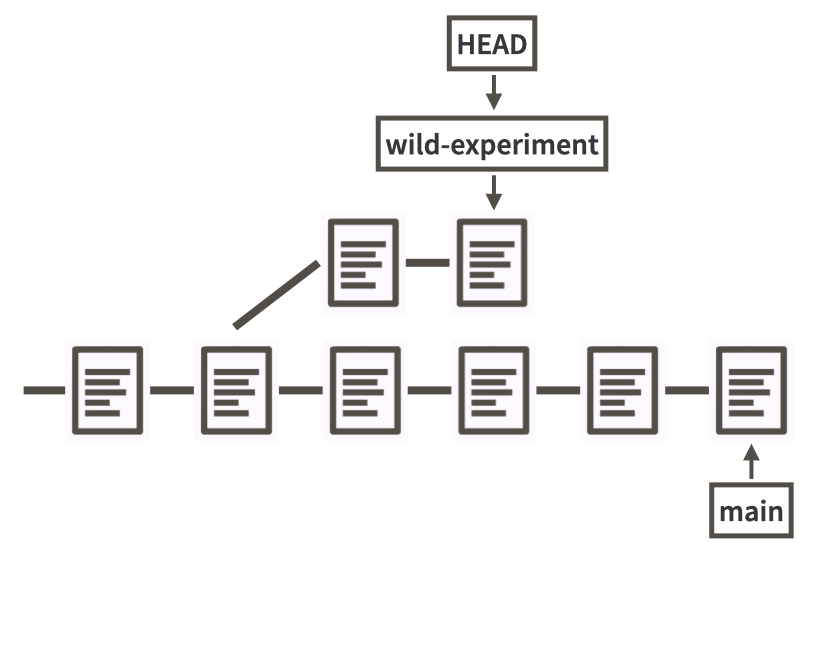

HEAD. This (almost always) resolves to the tip of the branch that is currently checked out.4 You can think ofHEADas a ref that points to the tip of the current branch, which itself is a ref, that points to a specific SHA. There are two layers of indirection. This is also called a symbolic ref.

- A tag.

Example:

v1.4.2. Tags differ from branch refs and theHEADref in that they tend to be much more static. Tags aren’t sliding by nature, although it is possible to reposition a tag to point at a new SHA, if you make an explicit effort. The most common use of a tag is to provide a nice label for a specific SHA.

If you’d like to make all of this more concrete, you can use git rev-parse in the shell to witness how refs resolve to concrete SHAs.

Here’s the general pattern:

git rev-parse YOUR_REF_GOES_HEREHere are some examples executed in the Happy Git repo:

~/rrr/happy-git-with-r % git rev-parse HEAD

631fee855db49d87f6c2a2cab474e89c11322bf4

~/rrr/happy-git-with-r % git rev-parse main

631fee855db49d87f6c2a2cab474e89c11322bf4

~/rrr/happy-git-with-r % git rev-parse testing-something

1eeb91d177b7cb5f9a0b29ebee3e6c0c8ff98f88Notice that HEAD and main resolve to the same SHA, since the main branch was checked out at the time.

testing-something is the name of a branch that happened to be lying around.

These refs can be used in all sorts of Git operations, such as git diff, git reset, and git checkout:

git diff main testing-something

git reset testing-something -- README.md

git checkout -b my-new-branch main24.2 Relative refs

There are also modifiers that help you specify a commit relative to a ref, e.g. “the commit just before this one”.

HEAD~1 refers to the commit just before HEAD.

HEAD^ is another way to say exactly the same thing.

Here are some examples executed in the Happy Git repo:

~/rrr/happy-git-with-r % git rev-parse HEAD~1

5dacec4950a3746310bb30704417a792302b044a

~/rrr/happy-git-with-r % git rev-parse HEAD^

5dacec4950a3746310bb30704417a792302b044aNotice that HEAD~1 and HEAD^ resolve to the same SHA.

Both of these patterns generalize.

HEAD~3 and HEAD^^^ are valid and equivalent refs.

I must admit that I am not a big fan of these relative ref shortcuts and especially not when reaching back more than one commit. I worry that I have some sort of off-by-one error in my understanding and I’ll end up targetting the wrong commit.

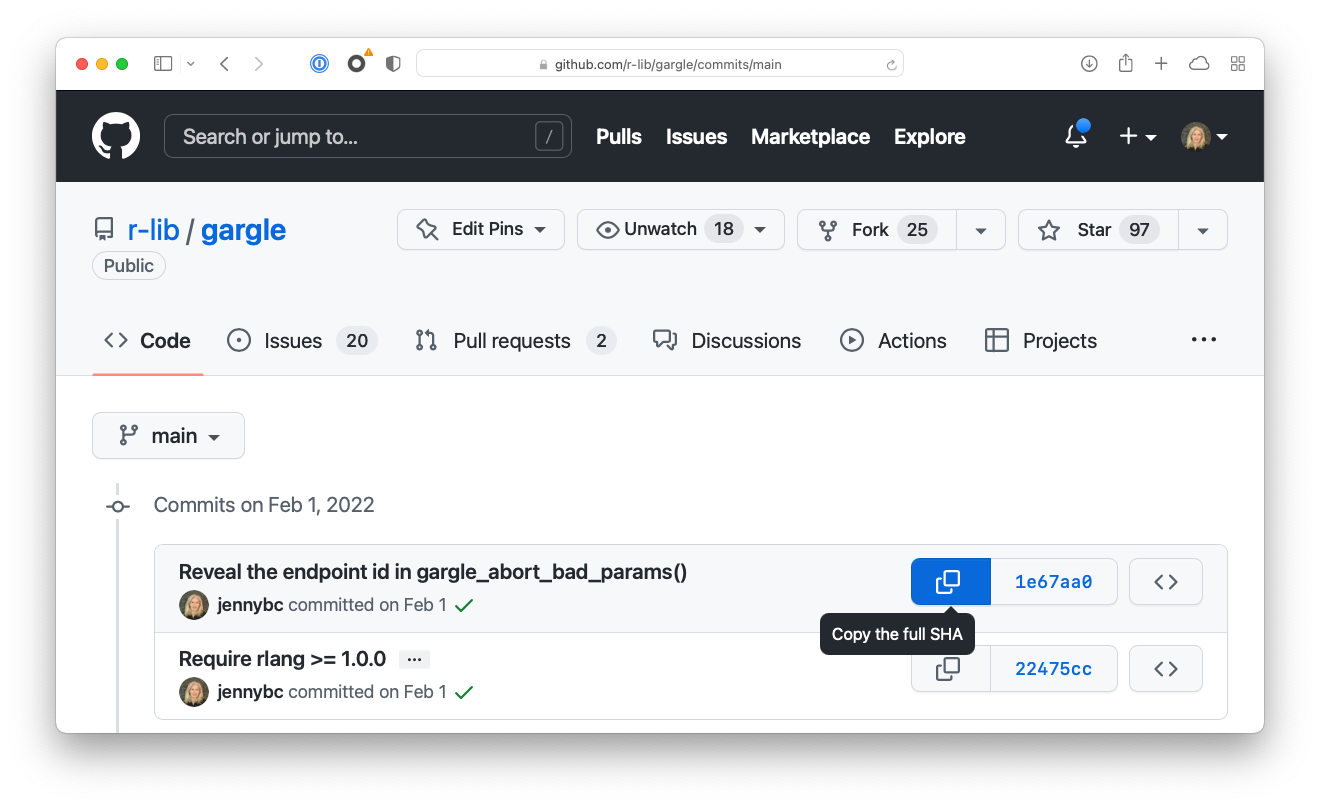

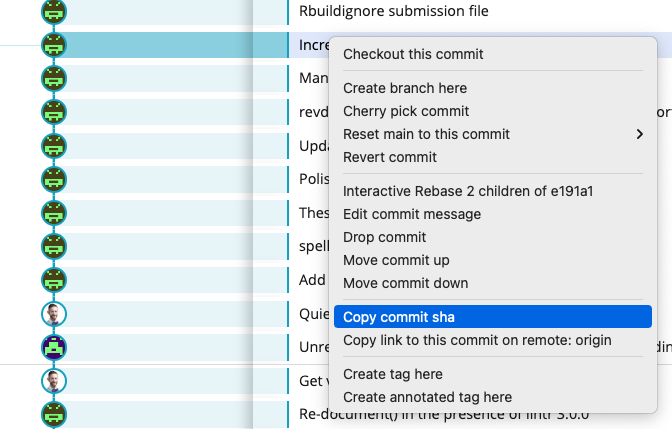

Tools like GitKraken and GitHub make it extremely easy to copy specific SHAs to your clipboard.

So when I need a ref that’s not a simple branch name or tag, I almost always lean on user-friendly tools like GitKraken or GitHub to allow me to state my intent using the actual SHA of interest.

I suspect that the relative ref shortcuts are most popular with folks who are exclusively using command line Git and are operating under different constraints.

There’s actually a rich set of ways to specify a target commit that goes well beyond the ^ and ~ syntax shown here.

You can learn more in the official Git documention about revision parameters.

In GitKraken, right or control click on the target commit to access a menu that includes “Copy commit sha”, among many other useful commands. If you’re using another Git client, there is probably a way to do this and it’s worth figuring that out.

GitHub also makes it extremely easy to copy a SHA in many contexts. This screenshot shows just one example. Once you start looking for this feature, you’ll find it in many places on GitHub.